Let’s begin with a postulate: there is either no “AI” – artificial intelligence – or every intelligence is, in fact, in some way artificial (following a recent talk by Bernard Stiegler). In doing so we commence from an observation that intelligence is not peculiar to one body, it is shared. A corollary is that there is no (‘human’) intelligence without artifice, insofar as we need to exteriorise thought (or what Stiegler refers to as ‘exosomatisation’) for that intelligence to function – as language, in writing and through tools – and that this is inherently collective. Further, we might argue that there is no AI. Taking that suggestion forward, we can say that there are, rather, forms of artificial (or functional) stupidity, following Alvesson & Spicer (2012: p. 1199), insofar as it inculcates forms of lack of capacity: “characterised by an unwillingness or inability to mobilize three aspects of cognitive capacity: reflexivity, justification, and substantive reasoning”. Following Alvesson & Spicer [& Stiegler] we might argue that such forms of stupidity are necessary passage points through our sense-making in/of the world, thus are not morally ‘wrong’ or ‘negative’. Instead, the forms of functional stupidity derive from technology/techniques are a form of pharmakon – both enabling and disabling in various registers of life.

Given such a postulate, we might categorise “AI” in particular ways. We might identify ‘AI’ not as ‘other’ to the ‘human’ but rather a part of our extended (exosomatic) capacities of reasoning and sense. This would be to think of AI ‘organologically’ (again following Stiegler) – as part of our widening, collective, ‘organs’ of action in the world. We might also identify ‘AI’ as an organising rationale in and of itself – a kind of ‘organon’ (following Aristotle). In this sense “AI” (the discipline, institutions and the outcome of their work [‘an AI’]) is/are an organisational framework for certain kinds of action, through particular forms of reasoning.

It would be tempting (in geographyland and across particular bits of the social sciences) to frame all of this stemming from, or in terms of, an individual figure: ‘the subject’. In such an account, technology (AI) is a supplement that ‘the human subject’ precedes. ‘The subject’, in such an account, is the entity to which things get done by AI, but also the entity ultimately capable of action. Likewise, such an account might figure ‘the subject’ and it’s ‘other’ (AI) in terms of moral agency/patiency. However, for this postulate such a framing would be unhelpful (I would also add that thinking in terms of ‘affect’, especially through neuro-talk would be just as unhelpful). If we think about AI organologically then we are prompted to think about the relation between what is figured as ‘the human’ and ‘AI’ (and the various other things that might be of concern in such a story) as ‘parasitic’ (in Derrida’s sense) – its a reciprocal (and, in Stiegler’s terms, ‘pharmacological’) relation with no a priori preceding entity. ‘Intelligence’ (and ‘stupidity’ too, of course) in such a formulation proceeds from various capacities for action/inaction.

If we don’t/shouldn’t think about Artificial Intelligence through the lens of the (‘sovereign’) individual ‘subject’ then we might look for other frames of reference. I think there are three recent articles/blogposts that may be instructive.

First, here’s David Runciman in the LRB:

Corporations are another form of artificial thinking machine, in that they are designed to be capable of taking decisions for themselves. Information goes in and decisions come out that cannot be reduced to the input of individual human beings. The corporation speaks and acts for itself. Many of the fears that people now have about the coming age of intelligent robots are the same ones they have had about corporations for hundreds of years.

Second, here’s Jonnie Penn riffing on Runciman in The Economist:

To reckon with this legacy of violence, the politics of corporate and computational agency must contend with profound questions arising from scholarship on race, gender, sexuality and colonialism, among other areas of identity.

A central promise of AI is that it enables large-scale automated categorisation. Machine learning, for instance, can be used to tell a cancerous mole from a benign one. This “promise” becomes a menace when directed at the complexities of everyday life. Careless labels can oppress and do harm when they assert false authority.

Finally, here’s (the outstanding) Lucy Suchman discussing the ways in which figuring complex systems of ‘AI’-based categorisations as somehow exceeding our understanding does particular forms of political work that need questioning and resisting:

The invocation of Project Maven in this context is symptomatic of a wider problem, in other words. Raising alarm over the advent of machine superintelligence serves the self-serving purpose of reasserting AI’s promise, while redirecting the debate away from closer examination of more immediate and mundane problems in automation and algorithmic decision systems. The spectacle of the superintelligentsia at war with each other distracts us from the increasing entrenchment of digital infrastructures built out of unaccountable practices of classification, categorization, and profiling. The greatest danger (albeit one differentially distributed across populations) is that of injurious prejudice, intensified by ongoing processes of automation. Not worrying about superintelligence, in other words, doesn’t mean that there’s nothing about which we need to worry.

As critiques of the reliance on data analytics in military operations are joined by revelations of data bias in domestic systems, it is clear that present dangers call for immediate intervention in the governance of current technologies, rather than further debate over speculative futures. The admission by AI developers that so-called machine learning algorithms evade human understanding is taken to suggest the advent of forms of intelligence superior to the human. But an alternative explanation is that these are elaborations of pattern analysis based not on significance in the human sense, but on computationally-detectable correlations that, however meaningless, eventually produce results that are again legible to humans. From training data to the assessment of results, it is humans who inform the input and evaluate the output of the black box’s operations. And it is humans who must take the responsibility for the cultural assumptions, and political and economic interests, on which those operations are based and for the life-and-death consequences that already follow.

All of these quotes more-or-less exhibit my version of what an ‘organological’ take on AI might look like. Likewise, they illustrate the ways in which we might bring to bear a form of analysis that seeks to understand ‘intelligence’ as having ‘supidity’as a necessary component (it’s a pharmkon, see?), which in turn can be functional (following Alvesson & Spicer). In this sense, the framing of ‘the corporation’ from Runciman and Penn is instructive – AI qua corporation (as a thing, as a collective endeavour [a ‘discipline’]) has ‘parasitical’ organising principles through which play out the pharmacological tendencies of intelligence-stupidity.

I suspect this would also resonate strongly with Feminist Technology Studies approaches (following Judy Wajcman in particular) to thinking about contemporary technologies. An organological approach situates the knowledges that go towards and result from such an understanding of intelligence-stupidity. Likewise, to resist figuring ‘intelligence’ foremost in terms of the sovereign and universal ‘subject’ also resists the elision of difference. An organological approach as put forward here can (perhaps should[?]) also be intersectional.

That’s as far as I’ve got in my thinking-aloud, I welcome any responses/suggestions and may return to this again.

If you’d like to read more on how this sort of argument might play out in terms of ‘agency’ I blogged a little while ago.

ADD. If this sounds a little like the ‘extended mind‘ (of Clark & Chalmers) or various forms of ‘extended self’ theory then it sort of is. What’s different is the starting assumptions: here, we’re not assuming a given (a priori) ‘mind’ or ‘self’. In Stiegler’s formulation the ‘internal’ isn’t realised til the external is apprehended: mental interior is only recognised as such with the advent of the technical exterior. This is the aporia of origin of ‘the human’ that Stiegler and Derrida diagnose, and that gives rise to the theory of ‘originary technics’. The interior and exterior, and with them the contemporary understanding of the experience of being ‘human’ and what we understand to be technology, are mutually co-constituted – and continue to be so [more here]. I choose to render this in a more-or-less epistemological, rather than ontological manner – I am not so much interested in the categorisation of ‘what there is’, rather in ‘how we know’.

Richard Caygill –

Richard Caygill –  Matthew de Abaitua –

Matthew de Abaitua –  Simon Ings –

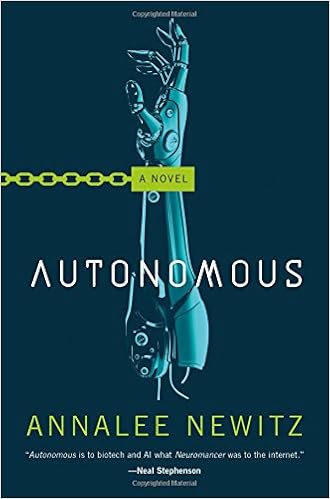

Simon Ings –  Annalee Newitz –

Annalee Newitz –